Story by Becky Hoag

Photos courtesy of Torsten Kjellstrand

The University of Oregon is on Kalapuya land. Several names that we take for granted every day, such as the Willamette and Klamath, are Native American names. In fact, there are many students and staff, as well as members of the surrounding communities, of Native American heritage.

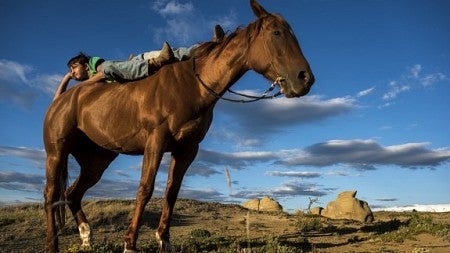

The SOJC project “Unvanished: Seeing American Indians in the 21st Century” aims to show what life is like for modern Native Americans. On the second floor of Allen Hall, an exhibit for the project features photography by photojournalist and professor of practice Torsten Kjellstrand, several SOJC students, and Native American photographers from reservations around the Pacific Northwest.

Although the exhibit’s photos were all shot within the last 18 months, the idea stemmed from Kjellstrand’s experiences before he even arrived at the SOJC. At age 8, he moved with his family from Sweden to Minnesota. Growing up in Sweden, the United States was always associated with cowboys and Indians in Kjellstrand’s mind, as that was what he had seen on TV.

Needless to say, Minnesota wasn’t quite what he expected. But he never lost his interest in Native American culture.

“I saw powwows, I saw casinos, I saw the occasional liquor store, and occasionally one of those stories that sounded like a compliment about the ‘noble savage’ kind of thing — people who can ‘walk more quietly through the woods,’” Kjellstrand said.

Convinced that there must be more to the seven reservations in the area to report on, he asked if he could write stories about basic community topics: language programs, weddings, promotions and other topics that would be reported in any other community. The soft-spoken photojournalist quickly built relationships that would stand the test of time.

Kjellstrand found that his “outsider” background was an advantage because it gave him permission to not know things. The people he met in native communities were happy to explain their traditions and daily reservation life to him.

“I have had a few situations where I have asked questions of elders in communities, and they explained to me a question I have asked,” Kjellstrand said. “And afterwards young people in the community will come to me and ask what the answer was because they didn’t know, but they felt like they were supposed to know.”

One of the reasons he found the Native American culture so interesting is that, although he did not know exactly what they had gone through, he could relate to some of the problems they experienced.

“Some of the issues you deal with as an immigrant are echoes of some of the issues that some Native Americans are dealing with as well,” Kjellstrand said, emphasizing that there are also many differences.

Kjellstrand’s academic lifestyle and a faculty grant he received from the SOJC’s Agora Journalism Center allowed him to dive deeper into the project. He and his team of five SOJC students worked to capture the modern Native American in their project. Some of the reservation members also photographed their community members, one photographer as young as nine. The project features seven different reservation sites, as well as made two videos.

One of the SOJC students who worked on the project is journalism senior Kara Jenness, a Kalapuya Indian who is part of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde.

The team was inspired by the photographer Edward Curtis, who had photographed Native Americans in the late 1890s to the late 1920s.

SOJC sophomore and project photographer Jessica Douglas remembered when Kjllstrand first mentioned Curtis to her. “He said, ‘Well, a lot of Native American communities have books of [Curtis’s] photographs,’” she recalled. “Once I told my grandma, she was like, ‘Jess! We have a book of Edward Curtis’ photographs!’”

Douglas is Native Siletz, and her grandmother left the reservation when she was 17 to live with her older sister. While Douglas always knew about the Siletz side of her heritage, it wasn’t until this project that she dove into her family’s history.

“I would be like, ‘Oh, Grandma! I learned about this today!’ and this would help her recall certain elements of when she was growing up and certain elements that are related to our culture,” Douglas said. “I think that has really shifted our conversation about our native identity and what that means to our family. It has definitely opened up a conversation I think that was not there before.”

According to Kjellstrand, because some of his team were of Native American decent, they provided insight into the culture and were able to photograph their fellow community members in a way that Kjellstrand likely could not.

“One of the most memorable parts was working with my family,” Jenness said. “I don’t think any of them, including my 3-year-old nephew, could really keep a straight face. We laughed about it and finally got the picture.”

The project group focused on capturing how the Native American people they photographed wanted to be remembered. When they asked each subject what they wanted to be remembered for, the answers were extremely varied. Pat “Judge” Hall wanted to be photographed in traditional attire, in part because he played Native Americans in Hollywood movies. Others wanted to be shown interacting with their family or in their daily lives. Skinny Campbell wanted to be shown as a good grandfather — and Kjellstrand confirms he is.

Some didn’t want to be photographed at all, but provided family photos for the collection instead.

“I hope people look at these pictures and see the humanity of Native Americans and not just a costume,” Jenness said. “Natives have been through horrific tragedies, but they are overcomers. They are resilient. You can see that in their faces.”

Kjellstrand says that this exhibit is only Chapter 1 of his project. He promised to return to the Kalispel reservation to photograph the school children every year until he can’t anymore. And he plans to continue the project until he feels it is no longer beneficial to do so.

“I’m not done,” Kjellstrand said. “I’m just getting started.”

“I’m not done,” Kjellstrand said. “I’m just getting started.”

You can see the Unvanished exhibit on Allen Hall’s second floor through the end of summer. Carolyn S. Chambers Professor of Journalism Damian Radcliffe’s Reporting II class helped write the captions for the photos, and another SOJC student is creating a website for the project. Kjellstrand hopes that this project with be displayed in other locations in the future as well.

Becky Hoag is a sophomore double-majoring in journalism and marine biology, with an environmental studies minor. This is her first term interning for the SOJC Communications Office. She also writes for UO’s environmental publication, Envision Magazine, and interns at Willamette Resources and Educational Network (WREN), a Lane County wetlands nonprofit. She is interested in being a research scientist and freelance environmental and scientific journalist. This summer, she will be attending the Oregon Institute for Marine Biology while working with the climate change-focused journalism project Science in Memory with other members of the SOJC. You can view her work at beckyhoag.com.