Every good story starts with a good interview. Few journalists know that as intimately as Professor Peter Laufer, the James Wallace Chair of Journalism at the UO School of Journalism and Communication (SOJC).

Laufer arrived at the SOJC in 2010 and has remained a crucial part of the school since. His work centers around borders, migration, identity and animal rights, investigating the complex social relationships that reside within each area.

He is also a fierce advocate and scholar of the journalistic interview. The UO anthology Interviewing: The Oregon Method, for which he served as editor, holds insight and guidance from three dozen expert educators.

We sat down with him to discuss how the interview grounds itself in every basic human interaction and what it takes to go beyond the list of questions.

SOJC: What do you think are some common mistakes people make when conducting journalistic interviews?

PL: I think the most common mistake is to come into an interview with a list of questions and say, “What's your name? Why are you wearing those overalls? Are they comfortable? Why is that the sweatshirt you chose? How come you have bangs?” and not have any engagement that is conversational, where there's a relationship developed. Not only do you as the interviewer get the information you're seeking, but you establish an interaction that allows you to learn about the person. And once you're engaged in an interaction like that, then you have the potential to get much more than just the dry responses to your list of questions.

SOJC: What are some top journalistic interviewing tips you would share with students, and why?

PL: Engage the interviewee as much as you can and develop a relationship as fast as you can, so that you're getting past the question-answer and rather are in conversation. And from that, you'll not only get a richer response, but you also have the opportunity to get more than that. The reveal is greater. And that's in large part because everybody likes to talk, and they like to talk about themselves most of all.

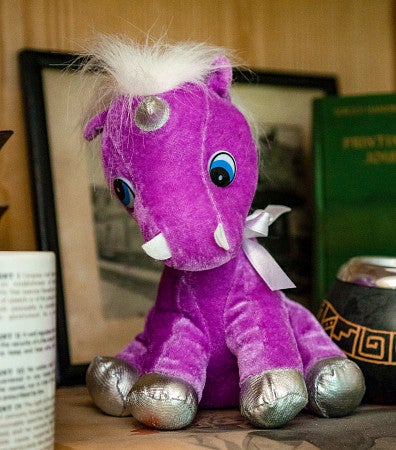

Another thing is when you come into somebody else's space, or even if you're not in somebody else's space, look around for something that strikes you that you think can help bring about that very fast rapport and hence pull something open from somebody. So, if you see something like, there I am with these guys on the Afghan-Pakistan border, then you say something about that, or something that's completely separate from news reporting, like, “What am I doing with a plush toy, a unicorn on the shelf?” These kinds of things help create a rapport.

The other thing is, say you have just written and published a book. The interviewer says, “Tell me about the book.” Well, that's a ludicrous question. Go find out about the book yourself, interviewer, and get some background so that you can talk to the person at a higher level. And the discourse has much greater potential to be substantive.

SOJC: What are you doing with a plush unicorn on your shelf?

PL: At the Lane County Fair, my wife played whack-a-mole and won three games in a row. I got to pick from what the arcade guy had, and I chose the plush toy unicorn.

SOJC: What does your involvement in the J-school look like now?

PL: One of the spectacular realities of journalism is that every day brings something new. And when one is privileged enough to combine being a practicing journalist with being a professor in a school like this, then every day is an enriching challenge. We are very lucky.

— By Kayla Nguyen, class of ’23

Kayla Nguyen, class of ’23, is a fourth-year journalism major and art minor working as a writing intern with the SOJC Communication Team.