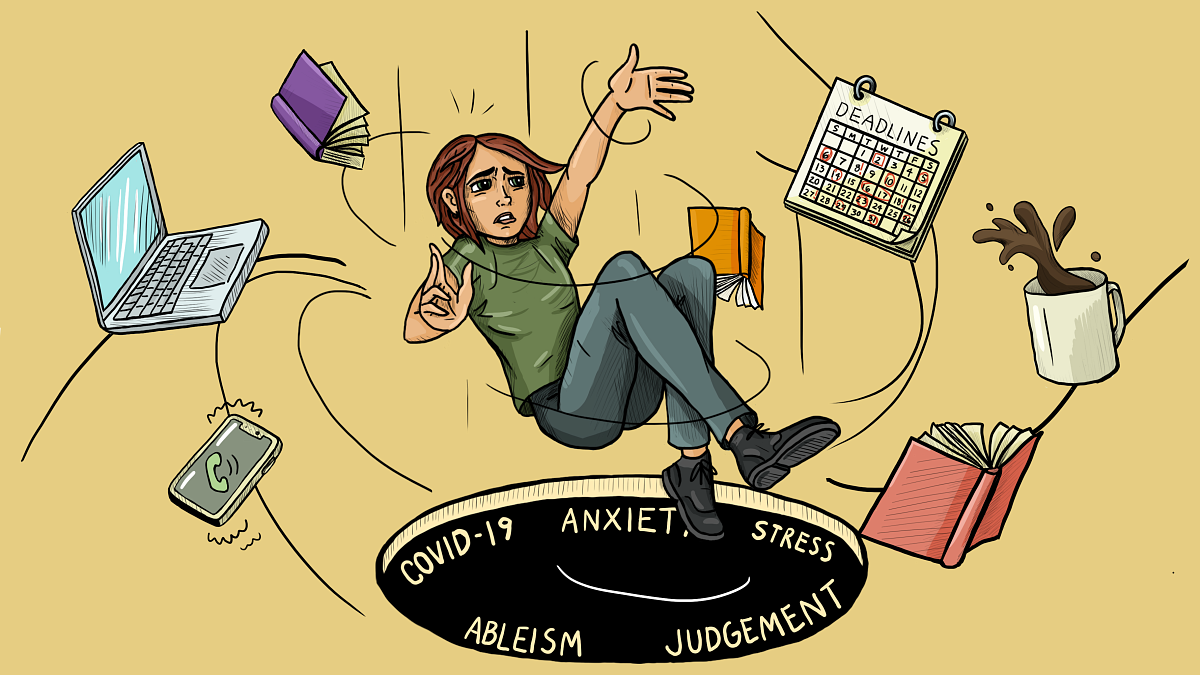

Navigating school with invisible disabilities and chronic illness is quite a journey.

I have had my diagnoses for a long time, and I have a well-established treatment plan. However, maintaining my health looks different when I am simultaneously tackling a full graduate course load, working part-time, in a committed relationship and trying to survive a pandemic. These things are a lot for anyone to manage, but they pose extra challenges for someone whose body is less tolerant of stress.

Ignoring my physical needs will cause weeks of mental fog, physical pain and deep fatigue. This can have ripple effects on my ability to succeed in school, creating a cycle of inefficiency and exhaustion. For obvious reasons, I try to avoid that by carefully managing my time, working ahead in my classes and scheduling rest days.

In short, being a student is a delicate balance of pushing myself hard enough to excel in school, but not so hard that I sacrifice my well-being.

But the most significant challenges I face come from systemic ableism.

Ableism is present when someone is othered for speaking, writing or thinking differently than what is considered normal. Unfortunately, academic environments often penalize students for expressing themselves in ways outside of prescribed norms. My cumulative GPA is 3.9, but in multiple instances I have had to explain my thoughtfully composed papers that diverged from traditional structures. Although I am proud of my unique perspective, it can be tiring to have to advocate for myself to be understood on a regular basis.

There can be social consequences for disabled students as well. Students in my previous program mocked me for the way I speak — which stems from a traumatic brain injury (TBI). As I share in this audio piece, I have worked hard on rehabilitating my body and mind, but one of the things that’s been hard to regain is that final bit of polish in how I present myself to the world. Although it can be devastating to be judged for a characteristic that is largely outside of my control, I am working on self-acceptance.

During my time in grad school, I have also decided to be more open about my history of TBI so that I can control my own narrative. And thankfully, there are always going to be people who can look beyond the superficial. I am fortunate to have crossed paths with many students who I now count as friends. I am also grateful to the instructors, faculty and staff who have been great sources of support in my journey as a neurodivergent student.

Unfortunately, ableism is also something I face in accessing my education.

Ableism is present in societal discourse about lifting pandemic safety measures because it will “only” affect people with underlying conditions. That’s unjust, full stop. That’s also more people than you might expect. I am one of them due to multiple chronic conditions. The argument is essentially that people like me should just stay home and let everyone else get on with their lives.

Yet staying home isn’t even a viable option these days.

It has become increasingly difficult to access resources as a remote student. In some classes, I have encountered significant barriers to remote access. It is demoralizing to have to ask for that access repeatedly, when I’m already navigating more hurdles than the average student. That said, some instructors have nimbly adapted to remote instruction in the past two years, and others are clearly invested in learning how to better support remote students. It’s a mixed bag.

More troubling, the University of Oregon lifted mask requirements at the start of spring term. While I understand the reasoning — this was in line with public health guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Oregon Health Authority, and it came at a time when case counts were going down — COVID is still a real concern for me, my fellow disabled and chronically ill students and other disproportionately impacted groups. Native Americans, Asian Americans, Latinx people and Black people have experienced higher hospitalization and death rates during the pandemic due to a combination of systemic inequities that target BIPOC (see the CDC statistics).

It is disheartening to see my university making choices that will make it even more difficult for students who experience systemic marginalization to access our education — an education into which we have invested so much time, energy and money.

Of course, I will continue to fight for my right to have a seat at the (digital and/or thoroughly sanitized) table. But the combined exhaustion of being a graduate student, being in literal survival mode for over two years, expending significant effort to be heard and yet being consistently belittled and/or overlooked — well, that tends to wear a person down.

Now would be a great time to have more allies in our corner, advocating for the continued inclusion of disabled and chronically ill students. To any would-be allies reading, I encourage you to step up and offer support to disabled and chronically ill students and BIPOC students — including advocating for improved accessibility.

And thankfully, there are already great allies in the university’s Accessible Education Center, the Portland Office of Student Services and the Journalism and Communication Graduate Student Association (JCGSA) Diversity Task Force. I encourage my fellow disabled and chronically ill students to utilize these resources. Remember your value and remember that you are not alone.

–By Jenni Denekas ’22

Jenni Denekas, class of ’22, is a Multimedia Journalism Master's student at SOJC Portland. Don’t call her inspirational, but please do connect with her on LinkedIn.