Craig Harris ’89 was no stranger to the word “sacrifice” growing up. At 13 years old, his life was uprooted when his father permanently departed, leaving him, his brother Corey and his disabled mother to lean on subsidized housing in Oregon City, Oregon. Day by day, they relied on welfare and food stamps to meet basic needs.

“I had to get free lunch at school,” Harris said. “I stood in line to get cheese and flour in high school, and I mean that’s pretty embarrassing. You’re 16 years old, and the other kids in the community see you standing in that.”

Despite the uncertainty of his childhood, that hardship is what inspired Harris to pick a career in journalism — one that would unfold over the next 32 years and take him all over the map.

“It wasn’t a very fun upbringing, but it really motivated me to be a journalist, to try to write about the underdog and right wrongs,” he said.

Harris’ interest in storytelling led him to the School of Journalism and Communication (SOJC) at UO. There, he began to lay the foundation for his life’s work.

During his freshman year, he quickly found an opportunity as a sports reporter with The Daily Emerald, UO’s student-run paper, where he covered women’s volleyball and basketball. At Allen Hall, he strived to make a name for himself by networking with multiple professors and walking in the footsteps of those who came before him. Among his mentors: former SOJC dean Duncan McDonald, narrative nonfiction professor and author Lauren Kessler, longtime journalist Steve Ponder and former SOJC dean Tim Gleason.

“One word I would use to describe my time at the SOJC is ‘challenging,’” he said. “The courses were incredibly tough, but I had great professors and learned grammar, interviewing and accuracy that have stayed with me my entire career.”

A career in investigative journalism

Since Harris graduated in 1989 with a degree in journalism, he has worked for seven major publications on a variety of reporting beats: The Olympian, The Oregonian as a suburban correspondent, The Salem Statesman-Journal as a political reporter, The Louisville Courier Journal as the statehouse reporter, The Arizona Republic as an investigative reporter, The Seattle Post-Intelligencer as a business reporter and USA Today as a business reporter.

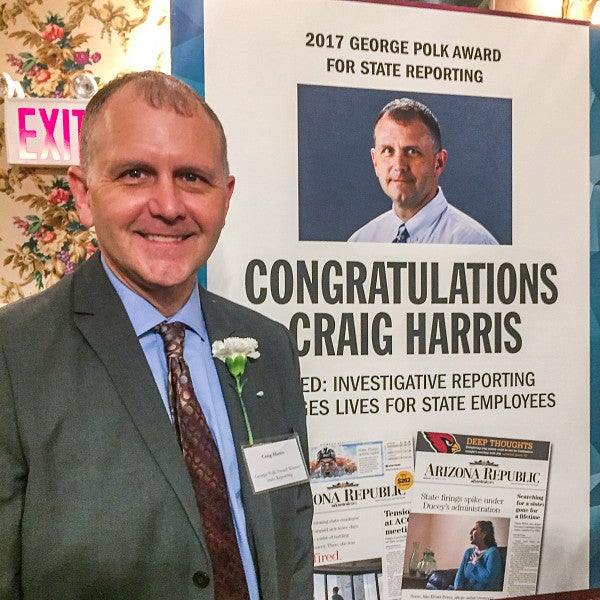

Harris said his longstanding history working in the media has yielded rewarding results. Some of his most influential stories were for The Arizona Republic. With several other reporters, he illuminated the unfair treatment of people of color and the elderly at a Veterans Affairs hospital in Phoenix, Arizona. Another story shed light on a pay-to-play scandal at the 2014 Fiesta Bowl, which sentenced CEO John Junker to prison. One of his investigative pieces restored jobs to masses of Department of Economic Security workers who were wrongly fired because of discrimination against their skin tone, gender, age or sexual orientation.

“You don’t get wins like that every day, but when you can write a story that helps someone who was disenfranchised — that’s what motivates me,” he said.

Harris said that news organizations support their reporters because of the importance of watchdog journalism — holding the corrupt accountable by revealing their shady activities — to society and our democracy. He added that the risks that come with exposing deception are worth it to uncover the truth.

“If you’re going to punch billionaires, or really influential people, or governors in the face, figuratively, you’re going to get people who aren’t going to like you,” he said. “I couldn’t care less who likes me. I think it’s really important to challenge those who are in power, watch those people and make sure that those who are underrepresented are not being taken advantage of.”

Expanding the reach of investigative journalism

Today, Harris is the managing editor-in-chief at The Coronado News, a 24-hour print and online newspaper that delivers free copies to every resident and business in the affluent city of Coronado, California, including a Navy base stationed there. The News recently published its third edition.

“We’re doing an investigative series on the sewage that comes up unmitigated from Tijuana and pollutes beaches in southern San Diego County,” he said. “I’m mentoring young reporters, and I’m running a newspaper for the first time in my life. It’s exhausting but fun.”

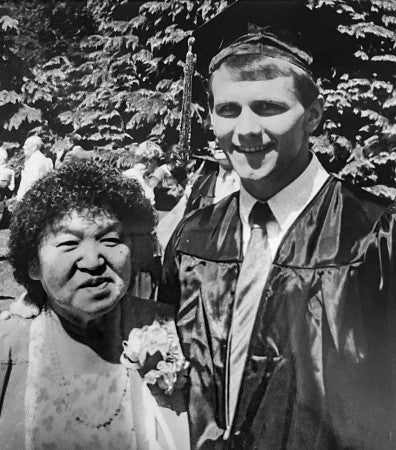

As Harris looks back on his life, he recalls feeling especially struck by his mother’s background during his adolescence. As a Japanese American, Chimiko Hamada-Harris was incarcerated at the Minidoka War Relocation Center in Idaho and Tule Lake Internment Camp in California during World War II.

Witnessing her struggle to provide for two kids as a single mother on welfare, he said, played a major factor in his decision to pursue journalism and make unheard voices heard.

“She made sacrifices every day, such as sleeping on the couch so my brother and I could have our own rooms,” he said. “Even though we were in a tough situation financially, we always had food to eat, and she made sure the bills were paid with the money she got from Social Security. She also was really good about letting my brother and I keep all the money we made from jobs, so we could buy our own clothes or do fun things with friends. Overall, she was an amazing woman.”

Making the most of every opportunity

From The Olympian to The Coronado News, Harris credits all his achievements to his SOJC education, expressing that it shaped his future and life for the better.

“I’m biased, but I think Oregon clearly is one of the best journalism schools in the country, bar none,” Harris said. “It helped me on a trajectory where I, a poor kid from Oregon City on welfare, made it all the way to USA Today, and then was able to run his own newspaper. And I could have never done that without the journalism school at Oregon. I’m incredibly indebted to what I learned there.”

With his college experience in mind, Harris recommends SOJC students “take numerous classes outside of journalism,” especially business and math classes.

“If you have a background in business journalism and you know how to read Securities and Exchange Commission filings, you will go very far in your career,” he said. “You can talk the language of CEOs or chief operating officers that you cover. So be as well rounded as possible.”

Currently, Harris said he hopes The Coronado News will sell enough ads to gain momentum and sustain itself and continue producing journalism for its community. Wherever he goes next, he will uphold his commitment to look out for the underdog.

“I think when you’re in journalism, and you can make a difference in someone’s life, you’ve actually changed the course of their life for something good,” he said. “You’ve done your job.”

—By Kayla Nguyen, class of ’23

Kayla Nguyen, class of ’23, is a fourth-year journalism major and art minor working as a writing intern with the SOJC Communication Team.